Episode 4: WINNETKA

Transcript

Jessica H: I'm Jessica Harper, and this episode four of WINNETKA.

(singing)

In the last episode I told you that thanks to the unfortunate birth of my little sister, our family was forced to move to larger quarters, much to my irritation.

But we didn't move far. We just bounced from one suburb to another, settling into our first house in the lovely town of Winnetka.

Winnetka is north of Chicago. And in 1956, when we moved there, it had a population of about 13,000 nestled in the shores of Lake Michigan. In some respects it was a lot like Lake Forest, a town that we had just left. But dad used to say he felt more at home in Winnetka in one week than he ever had in Lake Forest.

Eleanor H: This was a thoroughly middle class situation such as we had grown up in. Walking to school and living in neighborhoods where we knew the kids, and I could talk to the mothers, and it was all very cozy. So it seemed better to us than Lake Forest, where it was very hard to find people who were living that kind of life.

Jessica H: As for us kids, when we settled in Winnetka, Winnetka settled in us. For 11 years it was our hometown, in the way that made all subsequent stomping grounds seem slightly off.

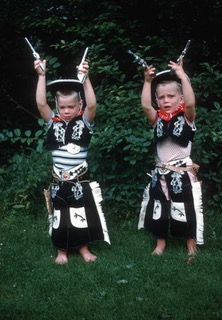

When I peruse the stacks of photo albums from the Winnetka years, the pictures bring on a tsunami of sweet and vivid recollections. Summer on Tower Beach, that hula-hoop contest, little boys on tricycles, and Thanksgiving dinner with Papa Harper. But just as vivid, and not represented in any photo album, are other memories of that time, and they are not nearly as sweet.

My twin brother, Billy, and I went on a nostalgic tour of Winnetka a few years back. We started by going down Sheridan Road to Tower Beach, where as children we spent hours every summer building sand castles. When we were teenagers, we'd spend hours on the same beach smoking pot and having sex.

Next on our tour, Billy and I went into town to where the sweet shop used to be. That was a diner that was our teen hangout, and also the place where my little brother Sam famously fueled up on a burger and fries before he robbed the jewelry store across the street. We passed by the apartment building where Lindsay's kidnapper took her back in 1959. And then we went up to Elm Street where I used to go to Charles Variety Store to by a Clark bar. That's a candy that is now extinct. Billy preferred to do his shopping across the street at Phelan's.

Billy H: Phelan's was a much better place to shop because you could pick up a comic book and slip out the door without the cashier seeing you.

Jessica H: (Laughs)

Billy H: (Laughs)

Jessica H: My favorite store was Betty's of Winnetka, where we high school girls used to go to buy perfect preppy garments, like that heather green sweater skirt combo by a designer called Villager, and my madras culottes.

Driving north on our tour, Billy and I passed the Episcopal Church where, in our day, there was an adulterous minister. And the library where I used to go a lot, not because I was devoted to literature, but because I sought peace and quiet, which were in short supply at home.

After passing our elementary school, Crow Island, which looks so tiny now, we ended our tour at 855 Willow Road. Our house looked, kind of, perfect to me when I was a kid. It was all white and symmetrical, normal, and respectable. But when it came to interior décor, my parents were iconoclasts. While many of their friends' living rooms would not have been out of place at the turn of the century, mom and dad bought Danish modern furniture and installed orange carpeting on the first and second floors. When you opened the door to ascend to the third floor, to the master suite, the carpet abruptly changed to lipstick red, and the wallpaper had this starry pattern on it that was very Austin Powers. It occurred to me much later that the design was meant to inspire, um, romance. And, as it turned out, that plan worked maybe a little too well. Our ranks were about to expand again.

But first, just as we were settling in, something happened that left me with a sense of foreboding. There was a plague. It's been recorded, and I am here to tell you, that in 1956 in my brand new neighborhood, an, an emergence of locusts, that was the largest anyone had ever seen anywhere, the- these locusts burst up from the ground at the rate of 1.5 million of them per acre of land. For some reason they do this in ... often and smaller, but still, staggering numbers. Um, they do it only every 17 years. They emerge, they party, and they drop dead. I don't know how they know it's 17 years. What, do they have these little calendars or something in there? I don't know.

Anyway, everywhere you looked you, you saw them in motion. It was just like the ground was alive with these packs of insects covering the ground, and the trees, and the swing set, and they were falling in your hair. I mean with every step you took, you, you'd kill, like, a dozen of them, uh, just with this horrible nasty crunch. And then you have to go home and scrape the little corpses off your shoes. Ugh.

This event worried me. I had not yet started going to Sunday School, so I was likely uninformed about, you know, Moses having that exchange with the Pharaoh about locusts being a sign of God's displeasure. But, still, I knew this was bad. Was this thing a harbinger of horrible things to come? I mean, were the good times over, giving way to a breakdown of the social order? Well, kind of. What happened next was that my mother gave birth to a second set of twins. Yeah, boys no less. Now that was biblical.

What are the chances that without the assistance of genetics or medical intervention, a woman can have two sets of fraternal twins? I don't know the answer to that question.

Now this was pre-ultrasound, so even though at nine months my mother was the size of a Volkswagen, she didn't know. But when she went to the hospital to deliver her fifth child, she would also be coming home with a sixth.

Eleanor H: No, indeed, I did not know. The doctor kept saying that I was so large, and I could scarcely move. But, but it was all water. And I thought how disgusting to be full of water. (laughs) I'd rather have twin.

Jessica H: I remember her on her birthday, July 11th, 1956, she was sitting out on the porch with a big glass of scotch balanced on her massive belly that unbeknownst to any of us was housing two full-term seven pounders.

So you had a big glass of scotch balanced on your stomach.

Eleanor H: Good heavens. Maybe that's why they're so nutty. I didn't know a thing about not drinking. And by the way, I think it was a gin and tonic, 'cause it was summer.

Jessica H: Charlie, and ten minutes later, Sam, revealed themselves the next morning.

Eleanor H: A son was born, and I'd been wanting another boy to keep Billy company. And, uh, so, the doctor said you've got your boy. And I s-, started to sit up and he said, no, no, lie down, there's another one coming.

Jessica H: (Laughs) Oh my God.

I had never seen my father look or sound the way he did on July 12th. He came home from the hospital, he sat down on the coffee table, and he said twin boys. He said it in this voice. I mean his whole aspect was like that of someone who had recently died.

Eleanor H: Oh my poor husband. He kept saying twins, twins, how am I gonna educate them all? And crying. Little did he know that everybody would drop out of college anyway and he wouldn't have to worry about educating.

Jessica H: When Sam and Charlie came home from the hospital, the effect was nuclear. My mother was suddenly managing six children under the age of eight, the youngest of whom were two infant boys. I mean, when I think about this, I feel the need to take a nap on mom's behalf. But my mother had a unique coping mechanism. She sang.

Eleanor H: Sambo, bambo, bibalow boop. I'm gonna make a great big soup. I'm gonna stir you all up in it, it won't take me more than a minute.It won't take me more than a minute.

Charlie, Barley, puddin' and cake, kiss your mother for for goodness sake. Kiss her once and kiss her twice, and now go out and try to be nice. (laughs)

Two little boys ran out the door, ran right down to the grocery store. Pissed on the vegetables, they pissed on the ham, nary ... what was that?

Jessica H: Didn't give a damn for ...

Eleanor H: Didn't give a damn for the grocery man.

Jessica H: (Laughs)

Eleanor H: I didn't really think about having a big family, because everybody I knew from school and college had, uh, at the very least, had four children. The rest had five, six. I didn't know anybody who had seven, but there's probably someone in there, and I felt like I, uh ... If there had just been two of them, I might have figured out who they were. (laughs)(Laughs)

But, as it was, I sort of thought of them, now I'm gonna say in a pond. But that's only because I'm doing a podcast....

Lindsay H: When they came home from the hospital, I was asked how I felt about my little brothers. And I said, famously, "I hate babies, and I hate boys."

Jessica H: Lindsay wasn't the only one who wasn't thrilled about the arrival of the twins.

Billy H: When dad came home from the hospital, he told us, well, you have two new brothers. They are twins. I was thrilled. Not only was gonna have one brother, but I was gonna have two brothers, and that was going to be three boys and three girls. The odds were now going to be even. So, finally they came home, and imagine my disappointment when I found out they weren't really brothers at all, they were just babies. Pretty much useless.

Jessica H: Apparently my father also had mixed feelings about having babies in the house, just as he had seven years earlier when Billy and I were infants. You may recall he didn't take kindly to the vocal exercises of my twin brother.

Charlie, unlike Sam, was also a serious vocalist.

Eleanor H: Charlie and Sam were very different. Sam tended to be the most, uh, quieter. And once you fed him and he was comfortable, he was happy to lie there looking at the miracle of his own hand. (laughs)

Jessica H: (Laughs)

Eleanor H: But Charlie didn't like lying around with nothing to do. Don't just leave him alone to try to solve his own problem.

Jessica H: Because if you did, Charlie would let you know about it, often to his detriment.

Charlie H: I had the crib right next to the door of the room. And, uh, somebody closed the door and it closed it on my fingers. And I don't know how long I was crying for. I'm sure I was very, very loud. I remember dad coming in, in a rush, and grabbing me, and slapping me to get me to shut up.

Jessica H: After several such episodes mom intervened. She told dad that if he hit her baby again she would leave him. That was a first for her, stepping in to protect a child from his father. Maybe after ten years of marriage she was less afraid of dad. She had gotten used to his anger and thought she knew its limits. Dad backed off his son, but sadly mom's new fearlessness did not last, and dad's surrender was only temporary.

I personally enjoyed our new celebrity status as a family with two sets of twins. Otherwise, I was pretty indifferent to our expansion. My life had been ruined already when Lindsay showed up, so I figured what the hell, bring it on. But one person in our family was very, very happy.

Eleanor H: There was a moment when I was left alone with the babies, and then I put on My Fair Lady, which was a hit show at that time. And I picked up one after the other of the children and danced up and down in the living room and singing, "I could have danced all night, I could have (laughs) danced all night..."

Jessica H: My mother got herself some domestic help in the form of a lady named Mrs. Davis. Mrs. Davis lived in rural southern Illinois. Like other women from her area, she came up north to the Chicago suburbs to make some money doing domestic work, going home to her family on the weekends. She couldn't have been older than my 37 year old mother, but she had the gray hair, false teeth, an extra hundred pounds of a woman who had, had a much more challenging life than mom did.

Sheltered as we were, Mrs. Davis' southern accent was new to me. And she said ain't, which up until then I had thought was a curse word. She was kind and affectionate with us, and hugging her soft body was very cozy compared to the embrace of my lean angular mother. I liked Mrs. Davis, until one day when I liked her less.

A friend of Mrs. Davis' came by to visit one afternoon. Mom wasn't around, and I was in the living room while the two women were chatting, and I was, just, kind of, casually eaves dropping. Mrs. Davis' friend said to her, "Well that's a cute dress." Mrs. D always wore dresses, nothing but. The one she had on that day was a lively green and purple plaid, and she told her friend that she had bought it at J. C. Penney's. Then she said, "I used to like this dress 'til I saw a (n-word ) wearing it. Now I don't like it no more." I froze. My father had taught me, in no uncertain terms about that word. That it was never to be spoken. And here was a grown-up, a caretaker in our house, speaking that awful word right out loud.

I was too young to know much of anything, but I was pretty sure that her use of that word signified a defect in Mrs. Davis. I could not reconcile Dad's firm instructions with her behavior. From then on I didn't trust her. I kept my distance, just in case she had some other evil up her green and purple plaid sleeve. I had no idea at that time that a certain member of my own family was just as evil as Mrs. Davis. I'll tell you about that in the next episode.

We were now officially a big family, big enough that our parents divided us into sections. The big three and the little three. While the big's rocketed around the neighborhood on our bikes, mom was tangled up with the twins. Until their arrival, Lindsay had enjoyed a unique closeness with mom. But, now, my little sister was, kind of, falling through the cracks. And when Lindsay was old enough to go to school, this had some scary repercussions.

Lindsay H: When I was in kindergarten, I walked to school and home from school by myself, six or seven blocks I think, down a pretty busy street. There were times when Diana's boyfriends, who were all ... These group of boys were all in love with Diana, who was in fifth grade, and, and they would come and get me and give me a piggyback ride home, tryin' to curry her favor.

Jessica H: Unfortunately, Lindsay didn't always have such willing escorts. And it was not that mom was neglectful, she was a devoted mother, but she was overwhelmed. So it happened that nobody taught Lindsay how to stay safe.

Lindsay H: One afternoon we were let out of Mrs. Bosworth's kindergarten at Crow Island School, and this woman came up to me and she said, "Hi your mom told me to pick you up. She said for me to buy you whatever you wanted at the Surprise Shop on the way home." So, naturally I went with her, got in the car, and she drove me to an apartment building, and I had never been in an apartment building in Winnetka.

And she took me up to this apartment, and there was an older woman there, and there was some conversation going on. And then she said, "Okay, I'm gonna drive you home now." And we got in the car, and I was sitting in the back seat, and I said, "Well are we gonna stop by the Surprise Shop like my mom told you that I could get a present." And she told me to shut up, sit back, and dropped me off somewhere near the school, I guess. Then I walked home. And she said, "Don't you ever tell your mother about this" in some very authoritarian way. And I never told my mother about it until 25 years later.

Jessica H: Her sudden loss of parental attention reverberated through Lindsay's childhood. I remember when she was maybe seven or eight, and she came to me, and she told me that a classmate had told her that she smelled funny. So I did an inspection, asked Lindsay a couple of questions, and I concluded that nobody had ever told Lindsay that you're supposed to wash your hair.

So I showed her how to turn on the water in the tub, and stick her head under and apply shampoo. I guess I'd been taught that particular grooming tidbit when mom had time for such teaching moments, which was before our family became so super-sized.

Lindsay H: Later on, I went to a psychiatrist for many, many years in New York. On my last visit to her, she said to me, "Well you know your whole problem is that when you were two and half, you had twin brothers that were born."

Jessica H: Still, Lindsay found some moments when she could recapture her closeness to mom.

Lindsay H: Probably my sweetest memory from childhood was when I would wake up from a bad dream and knew that it was my chance to be with mom. Uh, and in the middle of the night I would tip-toe into mom and dad's bedroom, and go around to her side of the bed, and tap her gently, and whisper that I'd had a bad dream. And without a word, she would take my hand and pull me in beside her in bed. We would curl up together and it was the most rapturous thing.

Jessica H: Apparently not satisfied that there was enough chaos in the house already, my father decided it was time to rename everyone. In the fine WASP tradition of gifting innocent children with preposterous nicknames, my father, Paul, was called Binky for much of his life. His sister, Lindsay, was called Sissy, and his brother, John, was Jinky. So they were Binky, Jinky, and Sissy.

My mother's family were no slouches in the name game either. Eleanor, Phillip, and Miriam were known as Cooie, Phippy and Minnow. Given their history, it was no surprise that my parents, Cooie and Binky were avid name changers with their own six kids, creating multiple identities for each of us. All the perfectly civilized names we were born with were swapped out for goofy alternatives.

Billy H: Dad was the master of nicknames. He called me variously Peepst, Probst, Pipe.

Sam H: My nickname was Pod. I don't know why, I don't know how that came up, but that's what I was called.

Charlie H: My nickname was Baba. The name Baba, evolved into Bob, and then Bobs Roberts, and then Boberts, and so on and so forth.

Jessica H: My big sister Diana Phillips Harper was Di-Di or Doots, and as for little sister, and Lindsay.....

Lindsay H: Lily was the main one. And from Lily it was Lotus Lily, and Lily Pad, and then it was Pad, and Pid and Moat, and Onah ...

Jessica H: My nicknames were Poteet, which was often shortened to Pote, Seeka, and then there was Pussy. I know, yeah, I know. But they say I had a feline cry when I was an infant. So they called me Pussycat, which was abbreviated to the hotter version when I was two.

While today it would seem cruel and unusual to send your daughter forward as Pussy. I grew up early enough in the 20th Century that the word had not yet achieved its current status. It was still used more by cat lovers than by porn enthusiasts, or the President. Even in early high school I could tell my blind date that my name was Pussy without raising his expectations. Plus, I was brought up in Winnetka, Illinois, a WASP nest if there ever was one. With friends named Gibby, and Tipper and Cici and Wickey, even a girl named Pussy could blend. But that was changing fast. By the late 60s the world was no longer safe for a Pussy.

I went to college on the east coast, leaving home and name behind. Like a spy, I switched identities completely, shredding all Pussy related documents and other evidence that my name had ever been anything but Jessica Randolph Harper. I know, the middle name is, kind of, iffy too. It's another WASP thing, but some things you just can't change.

As Lindsay said ...

Lindsay H: I always felt that dad's names for us all were coming from a very loving part of him. And that's why it always ... thought they were very special, and made me feel special, and also made me very nervous when he actually called me by my real name, which he did when he was angry.

Jessica H: But here's what Billy would say about that loving part of our father.

Billy H: With some sharp attention, one could detect dad's love for us from time to time. But anger was far more common and close to the surface. And we always had to be prepared for it to arise unexpectedly.

Jessica H: And that summer of '56 when the twins were born, Dad's anger was on full display.

Billy H: Physical violence was never, ever far from possible in any situation, no matter how small the child.

Jessica H: As I told you, dad had responded to mom's admonishment, after he hit his infant son, Charlie. But his temper rose like the temperature did as summer wore on. It didn't help his mood that work pressures had continued to build. His agency scored new heavy-weight accounts like Continental Airlines, and State Farm Insurance, and Morton Salt.

When after work he was met by the noise, heat, and chaos at home, he would just boil over. Billy, Mr. Trouble, had one of his worst run-ins with dad yet, when he misplaced the keys to the car.

Billy H: Dad had to get to the train and he was late. And he was looking for the car keys 'cause mom was gonna drive him. I couldn't find the car keys. He started hitting me, and, uh, hitting me across the face. I feel like I rolled across the floor he hit me so hard. He was just in a, in a rage like I've never seen before. Probably the scariest memory of his rages that I have.

Jessica H: One day that summer I skipped across the street to visit the neighbors. We came and went like that all the time without posting notice, that was our way, and I was old enough to stay safe. But apparently those rules tightened up in my brief absence. When I skipped back into our yard, dad grabbed me by the arm and slapped me across the face with stunning force in a fury that I had gone AWOL.

I had no doubt now that dad's outsized rage was fueled by things beyond the minor infractions of children. But that didn't occur to me when I was a young kid on the receiving end of it. That slap was so fierce, it didn't feel like discipline. It didn't feel like tough love. It didn't feel anything like love at all.

But that summer, and all through our childhood, what kept us in thrall to our wild father was that just as in some ways he could explode, he could flip sides and pull you in with what Lindsay called that loving part of him. As he did late that summer, when he taught us to fish.

Dad told me and Billy that we were going on a fishing trip, just the three of us. I thought this was a remarkable idea. I couldn't remember ever being in dad's company when there were at least three other people in the room. We would drive to a place called Fish Creek in Wisconsin to stay with friends named Mr. And Mrs. Smith, who had a cabin on the lake, and we would fish.

Before I even had time to wrap my mind around this idea, the day of departure came. We climbed into the car and did not buckle any, as yet, uninvented seat belts. And it was hot that July morning, so dad rolled down the windows, took off his shirt, and put on this old hat that he'd had in the Marines. Then he lit a cigar and put the pedal to the metal.

The warm wind whipped through the car, making my hair all crazy as we left the driveway, left Willow Road, left Winnetka, left the suburbs altogether and settled in for miles and miles, and hours and hours of watching the blue sky and the green corn fields go by.

And Dad leaned back, puffing on the cigar, and he started to sing, pulling material from the Harry Belafonte songbook. He was a big fan of calypso music. He binge listened to it, played it at every cocktail party. We kids grew up on it.

"Day-O, Day-O. Daylight come and me want to go home. Oh Mister Tallyman, tally me banana. Daylight come ..."

"Yellow bird, oh way up in banana tree. Yellow bird comes sing a sweet song to me." One of his favorites was, "Oh those wedding bells..."

Billy H: "Down the way where the nights are gay and the sun shines daily on the mountain tops. I took a trip on a sailing ship and when I reached Jamaica, I made a stop."

(All Harper kids continue to sing a calypso)

Jessica H: Maybe it was just because my view of him was unobstructed by all the family members who were usually blocking it, but as he drove, and smoked, and sang, my father seemed to be the fully visible version of a charming man I'd only caught glimpses of before.

The corn fields eventually gave way to a different landscape, one that was more woodsy, rocky, and, well, lakey. And we were in the heart of Wisconsin, fishing country. The Smith's were very good-looking, as they greeted us from the porch of their rustic, chic cabin. The were like Wisconsin's version of Brangelina.

Dad helped them feed us, and then he equipped us with fishing rods. He put that awful worm on my fish hook, although Billy happily impaled his own wiggly bait. Then he took us out to the pier to hurl that hook out there and wait. He told us what to do in the event that the red and white bobber dipped below the surface, indicating a catch. Although as I recall, my reaction to that signal was simply to scream.

Two days of fishing off the pier went by in a way that could be described as tranquil or boring, depending on how you feel about waiting for a fish to succumb to the charms of a worm. But in any case, the quality of that time with my father was so unusual. I wonder if I amiss remembering. Were his arms around me? His warm hands on mine? The same hands that so often terrified me, as he guided me while I gripped the fishing rod and whipped the hook and bobber out onto the lake, watching them break the surface of the water. Did that really happen for 72 hours? Was he really happy and relaxed in our company? Was I in his? Or was it just magical thinking? Maybe it was a little of both. But I knew there was one thing I still had to bear in mind.

Billy H: With some sharp attention, one could detect dad's love for us from time to time. But anger was far more common and close to the surface, and we always had to be prepared for it to arise unexpectedly.

Jessica H: And where did all that anger come from? I'm sure that as mom and Sam speculated, that PTSD had a lot to do with it. But I'm also pretty sure that there is more to it than that.