Episode 5: THE GRANDFATHER REPORT

Transcript

Singing girl: Down by the river where the green grass grows. There little Mary was washing her clothes. She sang, she sang, she sang so sweet that she sang Patrick across the street.

Jessica H: I'm Jessica Harper and this is episode five of WINNETKA.

Recently my sister, Lindsay, found a letter that I had written to my parents when they were traveling in California.

‘This is a letter written by you on March 29th, 1960. Dear Mom and Daddy, I'm sitting up on the third floor with Lindsay right beside me. We just got through watching Dennis the Menace. Today we went to Papa's house for lunch, it was lots of fun.’

Lindsay H: When we first got there, we got out of the car and Papa got a rifle and some bullets. We went out in the field and took turns shooting at a target. We each got ten shots. After lunch, we went outside and shot at a target with a Colt 36 pistol. I got one nine, and that was my highest. After that, we went to the man-made lake in the Jeep. We were climbing on the hills of sand and dirt when Billy spotted some blood. We went down the hill and saw a dead dog with a rope around his neck. Ugh. Are you enjoying your trip? I hope so. It's fun sleeping up on the third floor. Lindsay is joining me tonight. Have you gone swimming yet? In parentheses, hiccup. I get a tickle in my spine when I think about California with all its sunshine and oranges. Bring home a few, won't you? Love and kisses, Pussy.

Singing girl: She sang Patrick across the street. (laughs)

Jessica H: It's funny, I don't remember thinking of Papa Harper's house as fun. The day I recall best was one Easter Sunday, I think it was 1959, and it was the first time my grandfather put a gun in my hand.

Papa Harper lived in Libertyville, a high-end rural community about a half hour away from our house. Although we arrived before noon on that Easter Sunday, he was already nursing a cocktail. We seldom saw him without that accessory.

I think Papa Harper forgot, between our visits, what a hell a big noisy family we were. As we pulled up to his gray colonial house with its tidy white shutters, he'd wave cheerfully from the doorway. His white hair impeccably groomed, and he'd be wearing his smoking jacket and suede slippers. He'd smile in happy anticipation, as if he were expecting, you know, Winston Churchill or Elizabeth Taylor.

But when we piled out of the car, kind of like that clown act in the circus, how many Harpers can you fit in a green Ford, his smile faded and he retreated to the shadows of the foyer, probably to freshen his cocktail, while we were left to exchange awkward greetings with the lady of the house.

Papa's first wife, my grandmother, died before I was born, and now he was married to a woman who was 20 years his junior. Her name was Marianne, although some called her the preschooler. She was our, sort of, de-facto grandmother, although in my opinion, she was ill suited for the job. For one thing, she was only 42. I mean she was too young to perform grandmother duties with the grace and wisdom that job requires. Also, she was divorced. And now in those days, we kids thought of divorced people as living on the dark side, like criminals, or Judy Garland. We certainly didn't know any other grannies who were divorced.

But her worst quality was simply that Marianne didn't like us. Now to give her some credit, I don't think she fully realized when she married Papa, how many grandchildren he had. I'm not sure there was full disclosure. If she'd been allowed to do a prenuptial headcount, she might not have let Papa put a ring on it. Anyway, we didn't like her either. So there.

In addition to a feisty wife, Papa Harper had a lot of guns. And given his history, this made a certain amount of sense, as Billy explains.

Billy H: Papa had several army gigs in his life. His main thing was soldiering and drinking. That was what men did. And I think his first gig was in the U.S. Army Cavalry chasing Pancho Villa along the Mexican border during the revolution there. And then he was in the Army in World War I, and then he enlisted in the Marine Corp in World War II. Alcohol was an extremely important part of the whole texture of military culture. Men had to have their daily ration of rum, or whatever it was.

Jessica H: Which started Papa's love affair with drinking.

Papa's gun collection was substantial. Old rifles, mostly, which he displayed upright in a glass cabinet in the living room. He used guns to shoot skeet and, sometimes, critters. He also liked toting them around when, for a time, he served as the sheriff of Libertyville. This was not a challenging job in this rural community where little happened that required a law-keeper's intervention. But he enjoyed playing the part, as was evident in a photograph of Papa wearing a coonskin cap and wielding a rifle to fake arrest his neighbor, who happened to be Adlai Stevenson, II.

My grandfather was a man's man. Not just in terms of his macho love of firearms and bourbon, but when we visited the pre-dinner activities centered around my twin brother Billy. Papa took him for rides in his old beat up open-top Jeep, bouncing with thrilling recklessness across the fields of high grass. It was Billy who got to learn how to shoot skeet, while my sisters and I sat and watched in our darling Easter dresses.

In fact, I had so little interaction with Papa, that I have no memory of what his voice sounded like. I don't think he ever said much, Marianne did most of the talking. And when Papa did say something, it was usually to someone who was either grown up or male. So it was surprising, to the say the least, when on that fateful Easter Sunday he invited me to step outside for a little target practice. I couldn't imagine why, when he had so many choices, he had selected me for a one on one.

In honor of the holiday, I was wearing a pink and white checked dress with short sleeves and a white collar, which must have stood out nicely against the bleak landscape. Papa was focused and gentle. I wish I could remember exactly what he said to me, but I'm guessing it was simple instructions. No fussing around with kid-friendly chatter.

He showed me how to hold the pistol up and look through the site to see the big black dot that was in the center of the paper target he had tacked to a tree about 30 feet away. He aimed and fired, and the loud bang made my hands pop up to cover my ears a little belatedly. I saw a hole in the target, about an inch from the center.

Papa smiled a little at his result, and then he handed the pistol to me. I almost dropped it. I'd never held anything that size. It was so heavy. I couldn't imagine how those T.V. cowboys could twirl those things around on their fingers and then just deposit them neatly into their holsters.

My heart was racing a little bit. I was holding a weapon that could kill people, as I had seen it do on T.V., those cowboys blowing the bad guys off their horses every five minutes. But my grandfather was entrusting me with it. And it seemed, more for me, the chance to enter his good graces, to bond with him for the first time, and possibly forever.

In no time I'd be moving on to Skeet shooting. Knocking clay pigeons out of the sky with a hearty laugh, while Papa toasted me with his bourbon. Maybe I could be the one hanging on for dear life in his Jeep. I didn't want to screw this thing up.

I followed Papa's instructions precisely. Looking through the site, zeroing in my objective. When I fired, my arm jolted backwards into the socket. I lowered the gun with two hands, slowly, my eyes still on the target. But at first I couldn't tell where my bullet had pierced it, that's because it's hard to see a hole against black. It was a bulls-eye.

I turned to Papa, but even before my grin was fully realized, the way he was looking at me put me on red alert. Although it was tough to read the nuances, I knew he was not happy for me. He was something else entirely, not even in a happy family. And then I got it. It sunk in and sat in my stomach. He'd expected to outshoot me, of course, thereby establishing his superiority. But I'd upset the agenda, and he did not like being bested by a ten year old girl in a pink dress.

We went back inside and resumed our old relationship, the one where we avoided each other. And things stayed that way until he died a decade later of cirrhosis. I'm sorry things weren't better between us. But as I thought later that day and beyond, hey, Papa, could I help it if my aim was true?

In addition to Papa Harper and Marianne, we had a set of nice grandparents. We visited them every summer, way out west. There's a picture of the eight of us looking fairly pulled together for us, standing in front of, and getting ready to board the Denver Zephyr, which was the train that would take us overnight to Colorado.

When we were installed in a couple of compartments, this was close quarters, Mom fed us the picnic she brought. And then two gentle black men in white coats appears. They made up our fold-out beds with sheets that were so white and crisp, they made me understand what clean really looked like.

I loved falling asleep to the rhythm of a gently rocking train, and then the next morning going to the dining room. We were not an Amtrak nation yet. The tables were topped with serious linens, and rosebud vases, and we ate thick french toast with silverware that had the heft and the warmth of the real elegant thing.

But most mind blowing of all, was when you'd sit in a car that had a vista dome and watch the Rocky Mountains come into view. This was an astounding sight for a girl from a flat state. I remember once, as we saw the snow-capped peaks looming in front of us, I entered into my own private drama. Uh, this was something I did, kind of, often. Singing America the Beautiful under my breath, I could virtually hear the string section behind me. I brought myself to an emotional climax when I got to the lyrics about, for purple mountain's majesty, bringing myself almost to tears.

Mom's parents, Nana and Papa Emery met us at the station in their car that always had this particular smell, which is the same smell that my husband, Tom's, '67 Mustang has today. Kind of a funky mix of motor oil and sweat. My grandparents' car was much frumpier than Tom's. After The Great Depression, they never had any luxuries. Never the means to upgrade to a car like our green Ford station wagon, or a Mustang.

Unlike their Harper counterparts, the Emery's were always happy to see our super-size family. As grandmothers go, Nana was the real deal. Unlike Marianne, she was the proper age for the job. And she also had the right hair, all gray and poofy, like smoke around her face. She always wore lipstick and a pretty dress, and lady-like shoes with solid heels. While Marianne showed up all too often in madras shorts, or ski pants, or even the occasional cowboy hat.

In contrast to Dad's gun-totin', hard-drinking father, Papa Emery was unarmed and sober. Well he did have a civilized glass of bourbon at the end of each day, but then Papa Harper had that same ritual cocktail at the end of each hour. Mild and kind, Papa Emery always seemed to stand a few feet behind his lively wife. He was all handsome and smiley, but he was mostly silent. He'd lost his beloved career as an investment banker in The Depression, and he never really recovered his joie de vie. But he and Nana had shared a legendary love, and they'd raised five children. Cooie, Minnow, Fippy, Chuck, and John.

Mom's sister, Aunt Minnow, was warm and cozy, just like our mother. Like what we expected from their gender. It was the uncles who surprised us. Changed our lives in a way.

Billy H: When I was a child, I had an idea of what men were supposed to be like, and that idea came from Dad. It didn't come from anyone else. Dad was a very powerful man, very domineering, even, kind of, a bully. My three uncles out west were entirely different species of men that I was used to dealing with in terms of my dad. They weren't threatening or scary in the way that dad tended to be. I had felt comfortable jumping on them, or teasing them, or playing with them in various ways that I would never play with dad, because I'd be a little bit afraid that I would trigger some kind of rage in him.

Jessica H: We learned from the uncles that men came in another model, other than the one we knew best. They were such a cluster of good folk, and I wonder now how much that had to do with lineage. Nana came from a long line of ministers, including her father, and a beloved grandfather, who was the founding minister of the Church of the Pilgrims in Brooklyn. If it's a valid idea that quality of character can be a constant, running through generations in a family's history, then the Emery's were in fine position to benefit from their ancestry.

A recent review of the Harper family tree lends credence to that theory of character constancy. Papa Harper's actions often echoed those of his forebears. But in the case of this family, it's not in a good way.

When he was in kindergarten, my nephew Quinn, who's the son of my brother, Sam, interviewed dad about his childhood. This was for a school project, and it was called the Grandfather Report. Quinn recorded some very interesting things about my father, and my father's father. It starts with the basics. Dad was born in 1920 in Koblenz, Germany, where his father, Papa Harper, was stationed in the Army. Dad was given his father's name, Paul Church Harper.

A year later Papa Harper returned to his home town of Evanston, Illinois with his wife, Anne Lindsay White and their baby, Paul Jr., also known as Binkie. Papa Harper went into the advertising business, and his wife had two more children, John and Lindsay, also known as Jenkie and Sissy. The family lived with Papa's in-laws, William and Rose Lindsay White. William was in the clothing store business, and she was a dressmaker who brought high fashion to the ladies on the North Shore.

Papa Harper's father was William Hudson Harper, and he was a local journalist, and his wife, Grace Cook Harper, was a housewife. They lived nearby, and my great-grandfather, also, wrote a book called Chicago History and Forecast, which I just bought on Amazon. All the White's and the Harper's were of English and Scottish descent, and they came over to the states in the last 1600s, early 1700s. And, in fact, our ancestor William White came over on the Mayflower.

In Quinn's interview with dad, we also learned that as my father was growing up, he liked to build model airplanes and play football. His favorite radio show was “Little Orphan Annie.” Favorite movie was “Wings,” and he loved the song, “I wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate.” His favorite actress was someone named Honey Child Walker, and his favorite actor was George Arliss.

Speaking about his future, dad said he wanted to be an airline pilot or a teacher, and when he was asked what he loved most about his parents, he said about his father that he loved his storytelling and playing with lead soldiers. About his mother, he said he loved her good nature and sympathy. This evokes a very familiar picture in our house, and in most homes in my circle. The mom provided the emotional warmth, while the father was the activity director. Dad took this model and ran with it, taking our playtime and giving it a structure that was not always welcome.

Sam H: Dad wasn't a guy who improvised his intimate time. He didn't pop into the room, and plop down on the rug, and play with Legos with you. He needed the time to be organized, and scheduled, and executed. So he decided that he would pick hobbies for us. My twin brother got coin collecting and I got stamp collecting.

Jessica H: And as Papa Harper had down with him, Dad introduced Billy to war games.

Billy H: He constructed a box in my room. A full wall display case for lead soldiers. Some real antiques and some really beautiful things that his grandfather had had. He studied the histories of battles. So part of my arrangement with him, the most boring part, was him reconstructuring en- entire battles. There was a Civil War battle, there was a Napoleonic battle, and this was way over my head. But I much preferred to play with the plastic soldiers that you could kill. Throw tennis balls at and knock them down, that sort of thing.

Jessica H: Oblivious to Billy's disinterest, Dad took the toy soldier thing to the next level. He gave Billy this kit that he could use to make his own soldiers. So you would melt down these ingots of lead, and then pour them into soldier molds, and then you would sand them down, and then you would paint them.

Billy H: This was another one of those things, crafty things, which I just could not manage as a child.

Jessica H: Only Billy could turn a well-intended craft project into a towering inferno.

Billy H: What I ended up doing was finding that I could melt the lead, then I could melt paraffin candles on top of the lead and, which it would smoke. And if you lit a match, that smoke would catch on fire. So you have this column of fire, maybe four, or five, six feet tall. And, then, if you sprinkled water in it, the water would explode and there'd be this grand explosion with sparks and everything. That was a clear misapplication of my soldier-making kit.

Jessica H: So down time with dad was never really down time.

Sam H: He was a former Marine, and he didn't believe in sloth. Hanging out was not a thing that he did. There was no hanging out and watching T.V. or just, sort of, enjoying the moment. He was always moving forward. If he was watching T.V., then it had to be the news, or a documentary, or ... Saturdays were not to be lying around. You were to be out working in the yard, mowing the lawn, and clipping the hedges.

Jessica H: Dad's attitude about down time applied even on holidays. According to my nephew, Quinn's Grandfather Report, dad's favorite holiday was the 4th of July, because there were explosions all day long.

When he was a grown-up and a father of six, his favorite summer holiday was not so much about explosions. Thanks to a certain Winnetka tradition, he saw it as an opportunity to get his kids in prime physical shape and advance their competitive drive. This was especially true in 1961. See, every year Winnetka celebrated the 4th of July with crazed enthusiasm. As my sister, Lindsay, would say ...

Lindsay H: So the 4th of July was almost as big as Christmas. It was an incredibly exciting event. I remember school would get out in June sometime, and then it was just miraculous to me that it was almost the 4th of July.

Jessica H: First, the town had a parade. Participants included pretty much anybody who wanted to wear red, white and blue, and wave a flag, and go weaving through the streets to the strains of a marching band that was provided by the high school. Their destination was the village green. They'd all spill into this sweet little park that covered a couple of square blocks. I never enjoyed these parades much. I was too anxious about what was coming next.

When everybody was assembled in the park, there were the famous 4th of July foot races. All who were willing were divided into age groups to compete, running a distance suitable to their years. If you were in first, second, or third, or fourth place, you would get a medal. And when the races were done, the Winnetka family with the most wins got a trophy, a giant cup with the family name inscribed on it.

I thought this prize was incredibly beautiful, shining on the podium in the July sunshine. And since it was no doubt made of gold, I figured it must have cost at least $100.00. Plus, it represented the absolute validation of a family's worth. In other words, to me it was right up there with something you might find on Queen Elizabeth's mantle piece.

We kids all dreamed of winning that cup. And this year in particular, 1961, we had our best shot. It was a unique moment in time when the little twins were finally eligible to run, well they were almost five years old. And Diana, at 13, had not aged out yet as she would the following year. So we had six contenders. And not only were we fast, we had a trainer.

Dad also had his eyes on that trophy. He was a sucker for anything competitive. And for weeks before the 4th, he had us out in the back yard practicing.

Sam H: What I remember is the huge build-up to the 4th of July. There was training for the races. We had a little island of woods in the back yard that we did races around to train for the big day of the races. And ...

Lindsay H: I remember very exciting when we got a stop watch, so we could actually time ourselves.

Sam H: A lot of pressure to perform, I felt that. Um, and, um, fortunately we us-, we usually got medals. I think I never ... we, uh, got a medal every year.

Jessica H: Except when we didn't, as happened to Lindsay.

Lindsay H: And it was devastating. Then we got home and we were having a cookout, and I went and made a medal for myself. (Laughs) It was so sad. It was horrible. I think we had some ribbon, and I cut a little round thing, and I said ... maybe I put second place on it, or, or a winner anyway.

Jessica H: I also did not win a medal one year. And dad gave me a bracelet as a consolation prize, which made me feel even worse because the fact that he had gone to the trouble to buy a bracelet in case someone lost was an indicator of the outsize importance he placed on winning. I never wore that bracelet. To me it would be like stamping the letter L on my forehead.

Needless to say, we had competitors for the big trophy. The Ford family had done well in the past years, and we knew they'd be tough to beat. They were two up on us with eight kids, born a neat 18 months apart. So when they were lined up according to age, there was this perfect two inches difference in height between one and the next.

They were also perfect in every other way. They were all blonde, and Susie Ford, who was my age, and her sisters, all had hair that fell in a perfect flow to their shoulders where it curled into a sweet little flip.

Mr. Ford was a dentist, so he and all his kids had perfect teeth, which I knew because they smiled a lot, presumably because they were so happy about their hair. As they stood together grinning in their perfect matching white polo shirts, they looked like a Colgate commercial.

Next to the Fords, we Harpers were a rag-tag group. My hand-me-down shorts were too long, my top was too boxy, my pigtails askew. The boys' untucked T-shirts were wrinkled and withered from over washing, but we were fierce. This was in no small part due our need to please our coach. We huddled together eyeing our foe. Mr. Ford smiled in our direction and dad smiled back, if you can call it smiling when somebody bears their teeth and growls.

We all knew behind this friendly facade, we were in a fight to the death. We were like that era's famous West Side Story gangs, the Jets and the Sharks. Well, actually, we were, kind of, like the Jets facing off with the Osmond family.

The festivities began with the youngest group. The twins, Sam and Charlie, took their places along the starting line with the other five year olds. To signal the start, the master of ceremonies fired a gun heavenward, which, if you were on edge, and who wasn't, made you jump out of your skin.

The little ones tottered forward, many of them, with uncertainty as to what their mission was, while parents screamed encouragement. Some kids stumbled and fell, some reversed direction, and some simply sat down. This made it easy for the twins who had endured weeks of training to hold the course. Both Sam and Charlie won medals. But the little Ford boy did too.

It went that way for Lindsay, and Diana, and Billy too. They all won medals, but so did the equivalent Ford. Then it was my turn, up against my nemesis, Susie Ford. I had to win, it simply wasn't optional. I mean if I lost, as I had before, we'd fall behind. We wouldn't go home with that beautiful family cup. I'd let everybody down. Worst of all, I'd let down my dad.

My heart was pounding as I took my place in the starting line. I ran as if I were personally being chased by the bullet. My legs were churning like they had a mind of their own. Everything was just a blur of red, white and blue. People yelling, people yelling so much. Until at last, I felt that string that marked the finish line give way across my chest, and my legs shut down, and everything went into slow motion. And a lady took my arm and told me that I had won third place. Uh, huh.

Susie also took a medal, and another Ford kid picked one up, too, in his race. So, the Harpers and the Fords with an equal medal count had left the other families in the dust. There was one event left, which would decide which of the families took home the coveted trophy. Mr. Ford was pacing, the sun bouncing off his molars. Dad was pacing top, red-faced and intense as if he were coaching the Chicago Bears going into overtime.

The last event was the mother daughter race. The daughter would hop across the grass in a potato sack to her mother who was waiting on the other side of the field. And the daughter would step out of the sack, hand it to her mother, who would slip into it and hop back to the finish line. The gun went off, and Diana, who was already in this big burlap bag, went hopping, uh, maybe 50 yards across to mom. And Diana was in the lead, she was just ahead of that damn Lizzie Ford. She got to mom, she slips out of the bag, and she helped mom into it, and mom took off. And she held the lead that Diana had set.

She seemed really calm and sure, hopping along in her burlap bag towards victory. And Mrs. Ford lagged well behind mom, and a couple of other hopping mothers behind her. But mom hung in there. And she was almost there, she had maybe ten yards to go, and suddenly her gait changed. She stumbled, and we all gasped in unison, when as if in slow motion mom went down, falling solid. She tried to get up, but she was tangled up in that damn burlap.

Jessica H: The three other mothers breezed passed her to finish. Mrs. Ford came in third, it was a cataclysm. That Ford family would take home the trophy, and we'd never get a shot at glory again.

"Mr. Harper is conceding victory to Mr. Ford." ... the MC said, channeling Walter Cronkite, as dad approached the podium to shake hands with his opponent. Life would never be the same.

I'm not sure dad gave my mother a consolation prize, because 55 years after the events of July 4th, 1961, she still seemed inconsolable.

Eleanor H: Here were my children in triumph, and we were about to wi- win the whole 4th of July race situation. And then it was my turn to race, hopping along in a gunny sack, and I fell down and caused my whole family, uh, fame.

Jessica H: The Grandfather Report tells us that dad's second favorite holiday was Christmas. No surprise there. Luckily there were not athletic contests associated with that holiday, although it might have seemed like a marathon to mom and dad.

Children go where I send thee. Where shall I send thee? I'm gonna send these three by three. Three for the Hebrew children, two for Paul and Silas, one for the little bitty baby was born, born, born in Bethlehem. He was born, born, born in Bethlehem.

Mom bought gifts for all the cousins, and the aunts, and the uncles, and the babysitters. And we were enlisted to decorate the packages. I don't mean just drawing a snowman. Have you ever tried to cut a reindeer out of brown construction paper? And since it was Santa, you'd have to do that eight times. I found this tedious, but I developed a healthy respect for the well-wrapped gift.

My mother also wrote a poem to accompany every single gift, including the ones that she gave to us. The poems were along the lines of this one. "All the best things come in two's, somebody has got new shoes." Dad, meanwhile, was down in the basement for weeks in advance of the holiday, hammering, building, painting a beautiful thing that would be revealed on Christmas day.

Okay, spoiler alert. This particular year, which I think was maybe 1960ish, he built a puppet theater. Three wood panels joined with hinges. It was painted in black and white stripes with red detailing, and it had a window in the central panel for puppet display. And even, and this was the most amazing thing of all in my book, a tiny red curtain made of fabric you could pull across the window at puppet intermission.

Mom has said that Christmas Eve she and dad were always up 'til three a.m. They were wrapping presents, mom was writing poetry and stuffing six stockings. Dad was putting the finishing touches on the puppet theater. So they were pretty exhausted when we finally were released to rush downstairs to begin an unwrapping process that would take hours.

A baby was born in Bethlehem, itty bitty baby in Bethlehem. A baby was born in Bethlehem, itty bitty baby in Bethlehem. A baby was born in Bethlehem, itty bitty baby in Bethlehem. A baby was born in Bethlehem, itty bitty baby in Bethlehem. A baby was born-

Later that day Papa Harper and Marianne showed up for dinner. Papa was always hammered at this time of day, but on Christmas, oh yeah, grandtini time.

Our dining table, which had once been owned by monks, maybe a century or so earlier, was long and narrow and had hard benches on either side. In the middle of our lovely roast beef dinner, Papa apparently forgot the seating was backless. But he was reminded of this fact when leaning back to slug down a last drop of wine, he crashed to the floor, as my father would say, ass over tea kettle. This would not be the only faux pas pas of the evening. My grandfather had come bearing some very unusual gifts.

Charlie H: Papa always seemed to hit the nail on the head with these big, big presents. I mean he always had the big presents-

Jessica H: He did?

Charlie H: ... under the tree.

Jessica H: Papa Harper did?

Charlie H: And, so-

Jessica H: I never got them.

I don't recall ever being the beneficiary of Papa's legendary largess. But this particular Christmas, the gifts he gave Sam and Charlie were entirely memorable.

Charlie H: Sam and I were very much into the Civil War, partly 'cause Billy and dad would stage these big battles, re-enacting Civil War battles with lead soldiers that dad had inherited from Papa. We were definitely Yankees. We were in Illinois, the land of Lincoln.

Jessica H: Did dad encourage that affiliation?

Charlie H: Yeah. There was a very strong understanding, the Union was forever and that the Yankees had it right. And, certainly, slavery was a disgusting institution. Anyway, we got these huge packages for Christmas, and we very excitedly opened them up. And in it were confederate uniforms. There were cannons that came along with it. But the confederate uniforms, which were too small for us anyway, were completely the wrong side of the tracks.

Jessica H: Oh I wish I could interview dad right now. What must he have thought when his own father gave my little brothers confederate uniforms.

Charlie H: Which we made up for at our fifth birthday party, where we got everyone Yankee hats. Those were the party hats. The girls all got bonnets, and we pretended this big pile of wood was a Yankee warship, on which Sam and I were the captains.

Jessica H: What must dad have thought of this? Dad the union lover, the Lincoln worshiper. What did he think when the little boys dutifully tried on those confederate uniforms that Papa Harper had Santa Claused?

At the end of that grandfather interview that Sam's son conducted, there were a couple of interesting facts about dad's childhood. When he was asked what he worried most about when he was a child, he said he worried about his pesky little brother. He always got in trouble for torturing him. But more than that, he worried about his father's approval. But as dad grew up, neither of these concerns would be resolved.

Billy H: From my understanding of, of dad's relationship to his father, was that it was fraught. Papa was a Hemingway generation, and had that sensibility of what meant to be a man, a proper man. A proper man spent his time drinking and fighting wars. Essentially that was the main occupation of the gentlemen. Dad didn't really fit into that model. Dad loved drawing, he loved reading, he loved reading about history. But he wasn't interested in hunting, he wasn't interested in guns, he wasn't interested in that sort of thing.

His younger brother, John, however, was, and loved guns, and loved hunting. And, so, my understanding is that, uh, Papa put John, his younger brother up on a pedestal and ridiculed dad for not measuring up to that standard of manhood. It became so bad when dad was in high school, there was tension between the two of them. But that's the reason that dad was sent away to boarding school. Fountain Valley was a pointedly progressive school.

Jessica H: So he goes to this progressive school, and it's unlikely that what he learns there is consistent with the values of his father, who has seen fit to gift his grandchildren with confederate army uniforms. Then dad goes to Yale, where he apparently, unlike his father who went there before him, is exposed to, and embraces, and forms his own very liberal ideas.

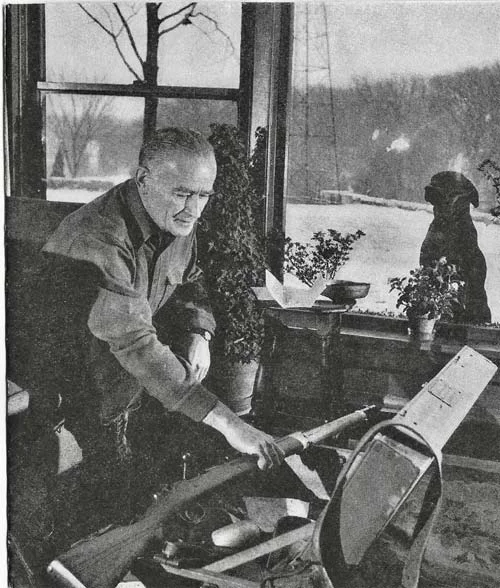

After Yale, dad joined the Marines in World War II, which must have pleased his war-happy pappy. But his little brother did him one better. John went to Korea in 1950. Not only that, but he got famous doing it. Uncle Jenkie wrote letters to Papa Harper that were published in an article in Life magazine December 3rd, 1951. It was titled "A Marine Tells His Father What Korea is Really Like." And there were two full pages. A big ol' picture of Jenkie in his Marine gear, and one of Papa Harper sitting in his favorite armchair with his black Labrador Retriever curled up beside him, and he's reading a letter from his son.

This picture of loving, and now celebrated communication, must have been tough for dad, since Papa Harper had impugned his manhood for being less of a gun hogger than his little brother. But that wasn't the only thing that probably troubled dad in this photograph of a father he struggled to connect with. Because in that photo was evidence of Papa's flagrant disavowal of a principle that dad held very dear. See, what Life magazine doesn't tell you is the name of that sleek black dog who sleeps at Papa's feet. It's spelled N-I-G. What's going on here? I'll tell you more in upcoming episodes.

WINNETKA is produced and edited by me, with digital editing and mixing by Andrew Schwartz. Additional help from Jeff Fox and Tom Weir. Original songs and music production are by me, with the exception of O Vos Omnis by William Harper. Special thanks to Oren Rosenbaum, Matt Cutair, and Ryan Rose. Jeff Umbro, Connie Fisher, Timothy Makepeace, and Susan Bolotin. Thanks and love, always, to Tom, Elizabeth, and Nora, and to my siblings, Diana, William, Lindsay, Sam, and Charlie. And, especially, thanks to mom.

For more information, please visit our website WinnetkaPodcast.com. We're also on Facebook and Twitter, and you can find us on Instagram at WinnetkaPodcast. This is a global original.